They say that verbs are the most essential part of speech.

Others argue that you cannot construct a complete sentence without a verb.

Well, I say that verbs are the backbone of the English language.

You see, both written and spoken forms of language are made up of different extensively dynamic parts. At the center of this complex web are verbs, which intricately link various elements to create meaning. They connect well with all the other seven parts of speech to form meaningful phrases and sentences.

In simple terms, therefore, you can think of verbs as the principal bonds or wheels that drive the English language.

But, make no mistake about it. While all verbs are equally important, they don’t exactly serve the same purpose. Each type of verb has its own syntax and grammar rules.

Now, to figure out how, when, and where they’re applied, you might want to keenly follow along as we dive deep into the world of verbs. This article explores the 5 primary types of verbs, plus the tertiary classes that accompany them. We’ve also included sentence examples to give you a practical idea of how the verbs are used.

For the sake of clarity, though, let’s start from the top. What exactly are verbs, and how do you even identify them in the first place?

Related: Types of Diction | Types of Adjectives | Types of Adverbs| Types of Nouns | Types of Pronouns | Types of Conjunctions | Types of Prepositions

What Is a Verb?

A verb, for starters, is a doing word or phrase. It basically describes the action that the sentence subject is carrying out. And by doing so, verbs- in most cases- establish a connection between a subject and an object.

Consider this sentence, for instance:

Tom cooked dinner.

In this case, “cooked” is the verb. It describes what Tom- who happens to be the subject- was doing. What’s more, it creates a link between Tom and the dinner, which is the object.

Similar examples of verbs include:

- Go

- Come

- Sweep

- Sing

- Eat

- Sleep

- Fight

- Collect

- Read

- Listen

- Speak

- Give

- Take

- Watch

- Touch

And so forth. The main idea here is describing the action.

It’s worth noting, though, that verbs don’t always have to be accompanied by nouns and objects. A verb can even form a sentence by itself.

For instance:

Cook!

Run!

While these are one-worded sentences, the verbs alone create meaning without the backing of nouns or adjectives.

Also, you might have noticed that while verbs are popularly described as doing words, they actually stretch beyond that.

Yes, that’s right- verbs don’t just describe actions. They also happen to explain events or states of the objects.

And no- not exactly in a similar manner as adjectives. Rather, you can think of it as the part of speech that expresses the occurrence or existence of something through activity-related words or phrases.

Confusing? Ok, here’s a good example:

You are happy.

In this sentence, there’s no distinct action being carried out by the subject “You”. Instead, the verb “are” describes the state of “being”, as well as the tense of the occurrence

The same principle applies to verbs such as:

- Is

- Was

- Be

- Can

- May

- Would

- Did

- Do

Now, let me guess. These examples probably trigger more questions than answers.

Fair enough. We’re looking into all of them shortly.

In the meantime, however, let’s find out how exactly you recognize a verb in a typical sentence.

How To Identify a Verb in a Sentence

Based on the examples we’ve discussed so far, you could start identifying verbs by spotting the actions.

For example:

We are playing soccer.

With “playing” being the action here, you can automatically qualify it as the verb.

But then get this- it turns out that’s not the only verb in the sentence. While the sentence itself contains just one distinct action, it carries more than one verb.

That said, it’s possible to identify the additional verb from its location in the sentence. It just so happens that verbs tend to be positioned right after nouns and pronouns.

Now, using this principle, we can pinpoint “are” as the second verb. Other similar examples include:

He is late.

We were there.

Another easy trick you could employ here is changing the sentence tense or time. As such, the word that subsequently alters its structure automatically becomes the verb.

Consider “He got in,” for example. You could change its tense into “He gets in”.

And there you have it. “Gets” becomes the verb.

Please note, however, that while these approaches can effectively identify many verbs, they are not adequately exhaustive. The fact is, there’s only one sure way to recognize all the possible verbs in a sentence. And it begins by understanding all these different types of verbs:

- Main Verbs / Action Verbs

- Auxiliary Verbs / Helping Verbs

- Modal Verbs

- Linking Verbs / State of Being Verbs

- Phrasal Verbs

- Transitive Verbs

- Intransitive Verbs

- Regular Verbs

- Irregular Verbs

So, without further ado…

The 5 Different Types of Verbs [Including Examples and Sentences]

Main Verbs / Action Verbs

Action Verbs, to begin with, are the specific words that indicate the type of activity the subject is engaged in. Some linguists like to call them “main verbs” as they are easily identifiable.

Examples include:

- Talk

- Wash

- Clean

- Write

- Sing

- Draw

- Take

- Finish

- Sit

- Jump

- Dance

- Go

And if you use them in a sentence, this is how they fit in:

Tom and Ivan talked about it.

Clean the car.

She wrote him a letter.

Sing a lullaby.

Going by these examples, it’s evident that action verbs can freely change their tenses to describe when the action occurred. For instance:

Although “She sang” and “She sings” indicate pretty much the same activity, the slight Action Verb variation shows the time difference in the two occurrences.

That said, you might have also noticed that Action Verbs give you the privilege of composing meaningful sentences without introducing additional words or subjects. For instance:

Buy!

Come!

Go!

Such clauses are often used to issue commands.

Helping Verbs / Auxiliary Verbs

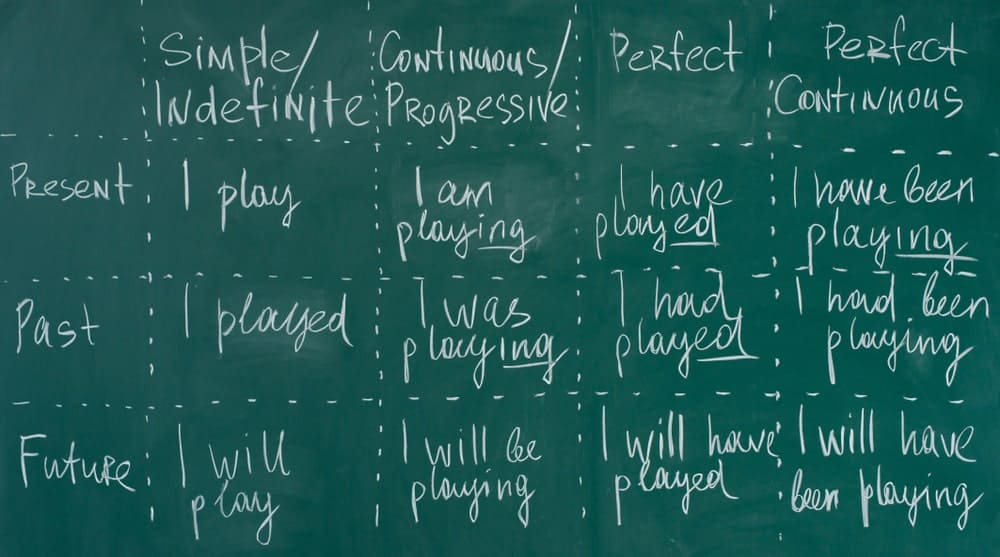

Abbreviated as “aux”, Auxiliary Verbs are pretty much the Helping Verbs that often accompany Main Verbs to indicate the specific tense of the action. They act as functional modifiers that create meaningful clauses by expressing emphasis, voice, modality, aspect, and tense.

In simple terms, therefore, you could say Auxiliary Verbs inform the audience when and how the action took place.

Examples include:

- All the forms of the verb “To Do”: does, do, did, will do, etc.

- All the forms of the verb “To Have”: has, have, had, having, will have, etc.

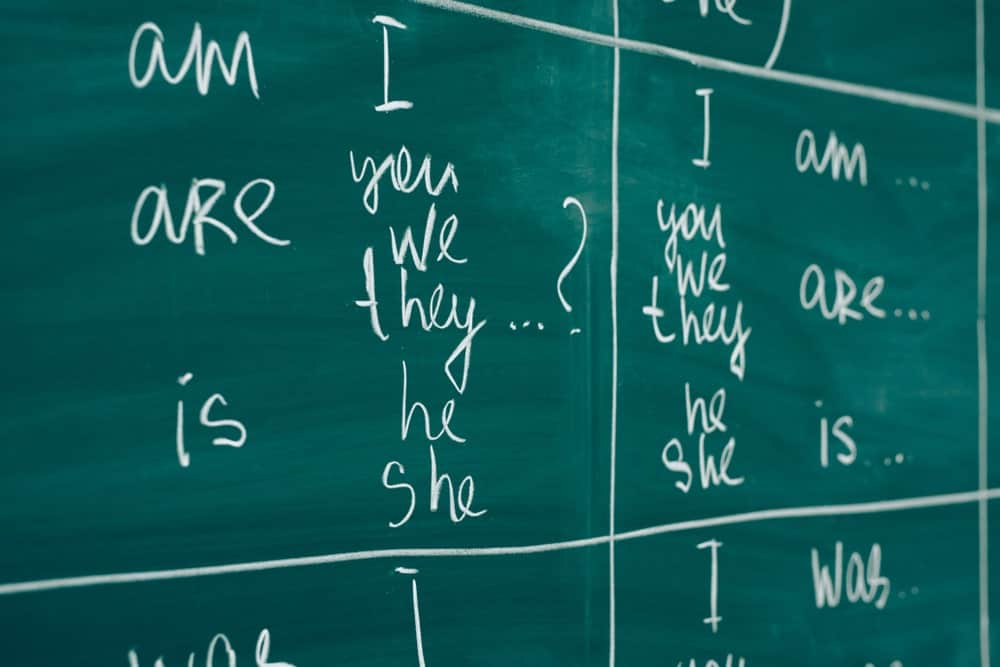

- All the forms of the verb “To Be”: am, is, are, was, were, being, been, will be, etc.

And here’s a typical sentence with an Auxiliary Verb:

We were eating dinner.

In this case, the Action Verb “eating” acts as the primary semantic clause. It lets you know the type of activity being carried out.

And to provide more meaning, it’s accompanied by an Auxiliary Verb “were”. It’s through this Helping Verb that you get to discover how and when the activity occurred.

That said, here are additional sentences that further demonstrate the application of Auxilary Verbs:

I am reading.

John has been wondering all along.

We did consider Jane’s thoughts.

We are leaving.

Jim has done his tests.

In addition to tense, Auxiliary Verbs are also used to signify the mode or state of the actions. Some common examples of such Helping Verbs include:

- May

- Might

- Would

- Can

- Should

- Shall

And this is how they are used in English sentences:

I might come home tonight.

You can go to school tomorrow.

We should see the manager.

Modal Verbs

While some linguists categorize Modal Verbs under Auxiliary Verbs, others choose to place them in their own distinct class.

Now, whichever side you’re on, one thing’s clear- Modal Verbs operate a lot like Helping Verbs. They traditionally go hand-in-hand with Action Verbs to express obligations, permissions, possibilities, and abilities.

I’m talking about verbs like:

- Ought to

- Would

- Will

- Should

- Shall

- Must

- Might

- May

- Could

- Can

You’re bound to find them in sentences like:

He can do it.

Tim could qualify for the finals.

We must count the money.

Jane should stay away from him.

From these examples, you could say “can” indicates ability, “could” expresses probability, while “must” and “should” are added to state obligations.

But, that’s not all. Apart from signifying possibilities, obligations, and abilities, Modal Verbs are frequently used to ask questions. And, in particular, they are placed right at the beginning of clauses to seek permission or clarifications.

Take, for instance:

Can I come to see you?

Would you be okay with this alternative?

Could you pass me the salt?

“Can”, “would”, and “could” turn the main clauses into questions that intend to politely seek permission from the audience.

Otherwise, you could alternatively use them in questions like:

Should he be punished?

Can you hack the test?

These are more like close-ended questions that seek basic “Yes” or “No” clarifications from the audience.

Linking Verbs / State of Being Verbs

We’ve already established that Auxiliary Verbs- such as “Is”, “Am”, “Are”, and other forms of “To be”- are often used along with Action Verbs. That much is indisputable.

But, it doesn’t end there. Turns out that such verbs are dynamic enough to be used even inactively in sentences without attaching any activity or action. So much so that, instead of modifying the Main Verb, the verb “To Be” ends up qualifying an adjective, noun, or pronoun.

This special class of verbs is fundamentally known as Linking Verbs or State-of-Being Verbs. Their principal function is to provide a connection between the subject of the sentence and the corresponding adjective, noun, or pronoun.

So, in short, you can think of them as verbs that explain the relationship between the main subject and the accompanying modifiers.

Consider this, for example:

Dave is a huge performer in Europe.

You are a fast runner.

In the first sentence, “is” describes how the subject “Dave” relates with the adjectival clause “…a huge performer in Europe”. It essentially explains the state of Dave being a popular entertainer in the continent.

Then in the second sentence, “are” acts as the primary link between “you” and “…a fast runner”. Or, in other words, the state of the subject being a quick runner.

Therefore, in a nutshell, you could identify Linking Verbs by simply reviewing the type of clause or word that follows them. If it happens to be an Action Verb instead of an Adjective or Noun, then you’re dealing with a regular Auxiliary Verb.

Phrasal Verbs

Action Verbs, Auxiliary Verbs, Modal Verbs, and Linking Verbs typically have one thing in common- they mostly exist as single words, but with multiple forms of tenses.

Here’s the thing, though. Verbs are not always that simple. Sometimes you’re forced to combine several verbs to convey the intended message. Such compound verbs are technically known as Phrasal Verbs.

And yes- they mostly come with two or three words. You essentially combine verbs, adverbs, adjectives, or nouns to form phrases with completely different meanings from their root words.

Take, for instance, the Phrasal Verb “Hand In”.

In itself, “hand” is normally used as a Noun or Action Verb. Then “in”, on the other hand, traditionally serves as an Adjective, Adverb, or Preposition.

Some of their practical applications include:

Hand me the shoe.

Take my hand.

He is in the room.

Count me in,

When you bring them together, however, “hand” and “in” collectively transform into a Phrasal Verb that offers a totally different meaning.

You could have the resultant phrase sentences like:

The professor told us to hand in the assignments.

You must all hand in your projects by tomorrow.

Other examples of Phrasal Verbs include:

- Point Out

- Think Through

- Face Up

- Bring Out

- Hand Out

- Make Out

- Go All Out

- Run Out

- Look Forward To

- Bring Up

Now, notice a consistent trend from the meanings of these examples?

Yes, that’s right. The meanings are not usually that direct. Rather, Phrasal Verbs predominantly serve as idioms with colloquial meanings.

Other Common Verb Classifications

Transitive and Intransitive Verbs

Transitive Verbs

Transitive Verbs are basically all types of verbs that are used to express an activity that passes from the subject to the object. The action itself is carried out by the doer, who then directs it towards another individual, thing, or place.

Here’s one sentence that shows the practical application of Transitive Verbs:

Sam wrote on the wall.

From that statement alone, you can tell that Sam is the subject or doer, while the wall is the recipient of the action. This direct link qualifies “wrote” as a Transitive Verb.

Other example sentences include:

I like that hotel.

They are playing a game.

Jim went to school.

The dogs have puppies.

Intransitive Verbs

Intransitive Verbs, on the other hand, are not ordinarily accompanied by objects. They are more like stand-alone verbs that indicate actions without distinct recipients. That means the subject or doer simply carries out the activity without necessarily directing it to a specific receiver or object.

You could, for instance, come up with a sentence like:

The car drove smoothly.

While “the car” is the subject, in this case, it doesn’t exactly pass the action to a specified thing or place. That means there’s no defined object. And so, we can conclusively categorize “drove” as an Intransitive Verb.

Here are additional examples of sentences with Intransitive Verbs:

The boat sailed steadily.

I work out regularly.

The cafeteria opens in the morning.

Regular and Irregular Verbs

Regular Verbs

A Regular Verb is just any type of verb that morphs into its past participle or past tense forms by simply affixing “-ed”, or “-d”.

Another term for this class is Weak Verbs- because all you need to do is add the standard endings to their root forms, and voila! They’ll automatically transform into their past tense and past participle versions.

This is where you place verbs like:

- Rain – Rained

- Wipe – Wiped

- Accept – Accepted

- Compare – Compared

- Bolt – Bolted

- Beg – Begged

- Advise – Advised

Irregular Verbs

Irregular Verbs, as you’ve probably guessed already, are the direct opposite of Regular Verbs. Their past participle and past tense forms don’t follow the conventional “d-or-ed” affix formula.

As a matter of fact, many of them don’t even add any extra affixes to their root forms. Some happen to retain their original structure, others transform by replacing syllables, while a few completely rework their wording structures.

They include:

- Sing – Sang – Sung

- Run – Ran – Ran

- Begin – Began – Begun

- Bend – Bent – Bent

- Beat – Beat – Beaten

- Lose – Lost – Lost

- Break – Broke – Broken

Over To You

And there you have it, ladies and gentlemen- all the five primary types of verbs, plus verb classes that collectively apply across the board.

With that, I guess it’s now over to you. You can go ahead and apply these lessons in your day to day conversations. We’ve even given you all the basic examples that you might need to figure out how the various categories of verbs are used. So, of course, you should have an easy time developing your language skills.

And while you’re at it, remember that some verb phrases and happen to fall into multiple classes. As such, you might want to approach everything here with an open mind.

Jon Dykstra is a six figure niche site creator with 10+ years of experience. His willingness to openly share his wins and losses in the email newsletter he publishes has made him a go-to source of guidance and motivation for many. His popular “Niche site profits” course has helped thousands follow his footsteps in creating simple niche sites that earn big.